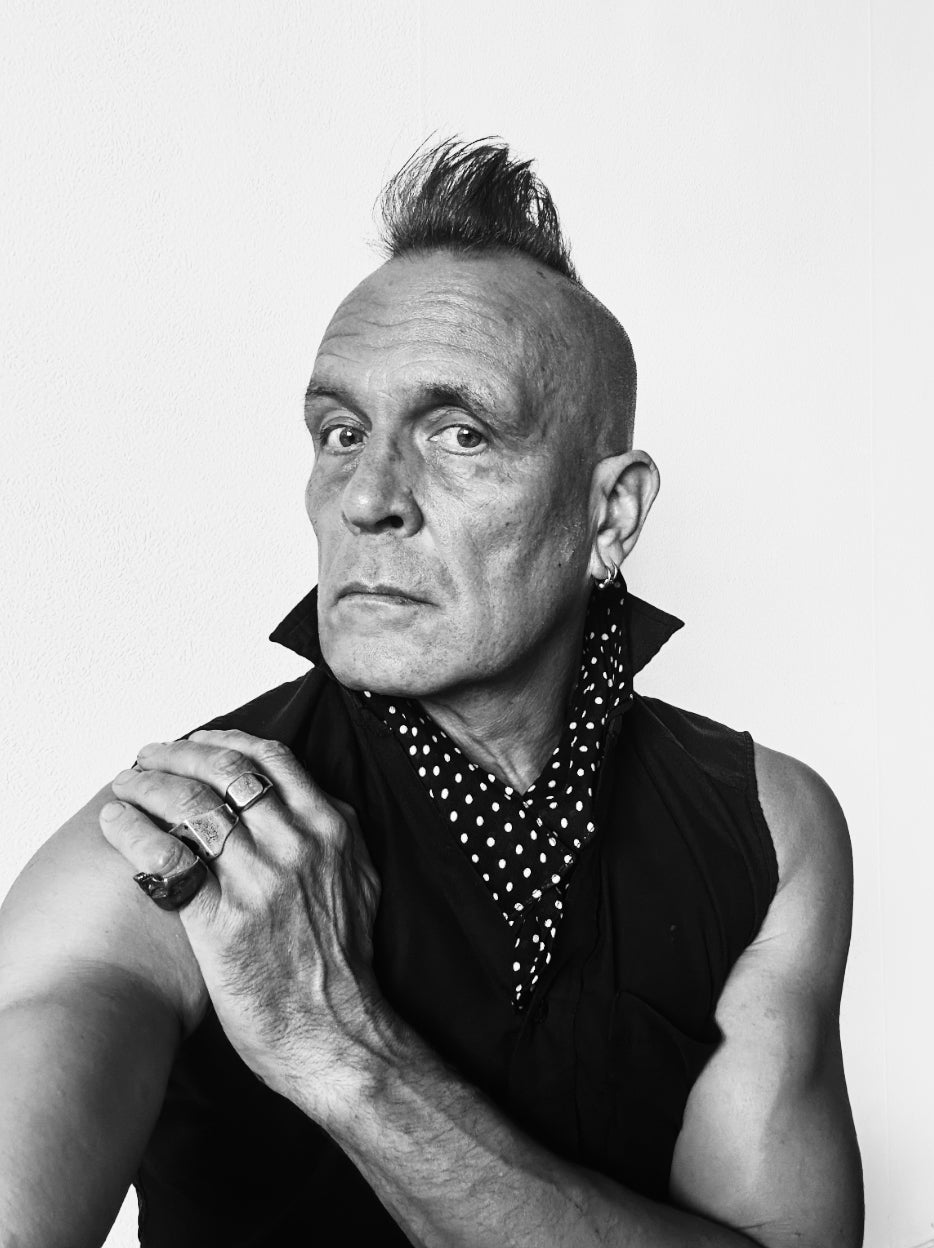

In conversation with Bobby Broom

Jazz guitarists don’t come much smoother or more accomplished than Bobby Broom. At 16 he performed in concert with the legendary Sonny Rollins, and over a career spanning forty years, has played and recorded with everyone from Steely Dan and Makaya McCraven to Kenny Burrell, Donald Byrd, Miles Davis and Hugh Masakela.

Like so many jazz players before and of his time, Bobby knows his way around a rig out. Take one look at the man and you see it — considered get-ups that are as liquid cool as his playing style.

We caught up with him to talk about his look, his past, and the evolution of jazz.

Tell us about your upbringing in 1960’s New York City. How were you introduced to music and jazz?

I was born and raised in Harlem during the early 1960s. I like to think of that time as the end of the Harlem Renaissance – an era recognised for the prolific creativity of Black Americans who’d migrated to northern cities - fleeing the formidable racism of the south.

I was 10 years old when I first heard and paid any attention to jazz, but I didn’t really know or care about that word until my dad came home from the barbershop with a stack of new records, one of which was ‘Black Talk!’ by organist, Charles Earland.

I wasn’t playing music yet, but I loved it. I recognised some of the songs from Top 40 radio which I listened to avidly. I fell in love with everything about Earland’s music – the sound, the groove, the arrangements, the solos (even though I didn’t understand them like I do now). I played ‘Black Talk!’ every day for months.

15 years later, Charlie happened to move to Chicago a few years after I’d relocated there. When I heard he was looking to form a new band, I knew it was my fate to play with him because of what he’d meant to me. That’s exactly what happened.

What about your fashion sense. Were there any early influences for you?

My parents were 40 when they had me, established in adulthood but young enough to want to be hip and trendy. They could’ve been models, and they dressed me up for everything. Outings, events, pictures.

My next major influencers would be the jazz musicians I apprenticed with, particularly Sonny Rollins and Sadao Watanabe. Sonny was always clean on and off stage. Silks and satins, classic shoes like Oxfords and Derbys by day, brand-new sneakers for the shows. That was back in the 1980s when Sonny was in his 50s.

He and his late wife Lucille bought me my first silk scarf when I was maybe 22 or 23. We were touring Japan and it was my birthday. I heard a knock on my hotel room door. I opened it to see nobody there, only a package on the floor. I looked down the hallway, nothing. Sonny must have snuck into the stairwell or the elevator. The scarf was off-white, beautiful. I still have it.

Sadao had a keen fashion sense too, right down to his accessories. I remember him wearing the coolest, small watches. Other influences were Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk. They used fashion to complete their personas both as jazz musicians and public figures.

Scarves and accessories are a big part of your wardrobe. Why is that? Do they hold any significance for you?

I was buying and wearing hats for years before I discovered that stingy brims suit my personality best. I dabble with wider brims sometimes, depending on my mood. As far as scarves go, I blame Sonny Rollins for that habit. He wore them regularly – as ascots, cravats, or just simply as scarves.

As a youngster, I looked up to these Black men in jazz. They were professional, dapper and well put together. Not only were they creating art, they represented the art form through demeanour and style. I believe style was their badge of honour and their suit of armour. So I began imitating and adopting that sense when I decided to become a jazz musician.

To me a scarf is an intriguing paradox. A subtle and easy to adopt piece that can be perceived as a bold personal touch.

Of all artists, musicians seem to be among the most style conscious. Why do you think that is?

I think it’s because of the on-stage persona of the musician and how fashion is used to enhance and amplify that. It can become an extension of a musician’s creativity.Sometimes, depending on their personality, it can carry over into their everyday life.

How important is a stylistic flourish in life?

Well, first and foremost, it helps to add a personal touch – whether in fashion and art (in my case, music), as well as writing and speaking.

It can help an individual or group distinguish themselves.

I think stylistic flourishes of any sort are to some extent a conscious choice. In order to maintain and develop upon them, one has to have a certain type of desire and awareness that they exist.

To build on that a little, are stylistic flourishes – solos, if you like — more or less vital in the modern day than they were in past eras?

I would say that flourishes as important as ever and we still use them for the same purposes. Although in the modern era, they may seem to have intensified — much like everything else — in the ways that we perceive the arts, entertainment and politics.

What were the fashion trends within jazz in the ‘60s and ‘70s? Are there any that have carried over?

The ‘post-bop’ musicians influenced by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Thelonious Monk took style to a new level. Monk was a towering figure who used fashion to distinguish himself on stage and in society. He wore berets a la the beboppers, but who else could pull off a woollen Karakul hat on stage?

The ‘hard-bop’ musicians like Sonny, Miles, and to some extent Roy Haynes and others – guys who played with and were mentored by Monk – all adopted a certain fashion flair and consciousness. This translated to all types of articles. Their clothing, shoes, accessories. Everything was considered.

Two Jazz generations later, in the 1980s, “the young lions” emerged. Wynton Marsalis, his brother Branford, Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison and others from my peer group wore suits, a jazz tradition. That continues today with tailors like Rahman Fashions in Hong Kong benefitting greatly from the tastes of many modern-day jazz legends.

What about the evolution into the ‘00s? Is there a typical mode or change in jazz styles that you’ve noticed over the last 20 years?

Musically speaking, it’s like I said: intensification is the order of the day. Heightened dynamics really seem to happen as new generations develop their skill levels. Because we live in a visual information-age, young musicians are far more skilled in the execution of jazz. However, this doesn’t always mean that the music evolves.

Trends come and go, but what is substantive joins the realms of the classics and becomes lasting. I imagine the same can be said of fashion. There are some clothes that I bought 20 or 30 years ago that I can still wear, and some that I must donate.

On that same note, how has your own attitude towards music and fashion changed in the past couple of decades?

Well, like with the hats, I’ve had to figure out what works best for me. When I finally realised or accepted my voice on the guitar stylistically, I could begin to do the things I wanted to do years prior; like playing classic rock tunes from my childhood. No one can say that the way I play “Happy Together” by the Turtles, or “Stand!” by Sly and The Family Stone isn’t jazz. Similarly, I feel most like myself wearing a scarf. And to pull that off, I must be conscious of the rest of what I’m wearing.

What does the future hold for jazz? What and who excites you about the genre?

At this point in the game for me, one of the most exciting things about the music is hearing new musicians, even those that aren’t necessarily young. There’s still so much jazz being created, there’s just no way to be aware of everything.

A little over six months ago, I started a radio show that broadcasts from the university where I teach – Jazz Spectrum, on WNIJ, from Northern Illinois University. It’s a two-hour that broadcasts a couple of times a week, and I get to play whatever I want. So that encourages me to stay abreast of new music, and to revisit and become aware of classics and other things that I’ve missed along the way.

The great thing about jazz is that it’s an indigenous, American music. So, because of that and what it represents, it will absorb and morph but always keep its core characteristics and spirit to sustain itself. Jazz music is made to last. Each new generation of players can attest to that.

To find out more about Bobby, you can visit his website here